Why Letter Names and Sounds Matter—and How the Active Alphabet Gets It Right

- activealphabet

- Jul 27

- 4 min read

When it comes to early literacy, one foundational skill consistently stands out in the research: letter knowledge. In fact, decades of studies have shown that a child's ability to recognize and name letters is one of the strongest predictors of future reading success (Chall, 1967; Adams, 1990). But how we teach letters—and how we connect names to sounds—can make all the difference.

What the Research Says

A landmark study by Piasta, Petscher, and Justice (2012) found that children who enter kindergarten knowing at least 18 uppercase and 15 lowercase letter names have a much higher chance of achieving reading proficiency by the end of first grade. That’s a clear benchmark with major implications for preschool and kindergarten instruction.

Just as important is how we teach those letters. A 2010 study by Piasta, Purpura, and Wagner demonstrated that teaching letter names and letter sounds together is more effective than teaching sounds alone. This dual-focus approach supports more robust letter-sound acquisition, helping children make meaningful connections between visual symbols and spoken language (Piasta, Purpura, & Wagner, 2010).

Additionally, research has shown that exposure to both uppercase and lowercase letters significantly improves children's ability to name them. Fry (2004) and Gerde et al. (2019) found that presenting both forms of the alphabet not only supports recognition but also helps children use their knowledge of uppercase letters to better understand lowercase forms (Pence et al., 2010).

Finally, while there's no single "right" order for introducing letters, research supports a practical, purposeful progression—starting with frequent consonants and short vowels to quickly move students toward decoding simple words (Roberts, 2003; Shaywitz, 2003).

How the Active Alphabet Aligns with This Research

The Active Alphabet foundational literacy system is built to honor and apply this research in real classrooms with real kids. Every element—from the characters to the sequence—was intentionally designed to support early readers where they are and move them toward confident, joyful literacy.

Names + Sounds from the Start

Each letter in the Active Alphabet is introduced through a character that ties the letter name, letter sound, and an alliterative action together in a meaningful context. For example, “Marching Moose” introduces /m/ with movement, imagery, and fun—all while reinforcing the name “M.”

This integrated approach reflects what the research tells us: when kids learn letter names and sounds together, they’re better able to internalize the relationships between them (Piasta, Purpura, & Wagner, 2010).

Intentional Letter Order

The Active Alphabet does not follow the traditional ABC sequence. Instead, letters are introduced in an instructional order that prioritizes early success in phonics and word building. Children meet high-utility consonants and short vowel sounds early on so they can begin reading and writing real words quickly.

This sequencing echoes research recommendations to prioritize letters that enable fast application in decoding (Roberts, 2003).

Uppercase and Lowercase Exposure

Every Active Alphabet activity, from skywriting to center-based tracing, ensures children engage with both uppercase and lowercase letter forms. This aligns with the benchmark that students should recognize both cases by kindergarten’s end—setting them up for success in reading print-rich texts (Piasta, Petscher, & Justice, 2012).

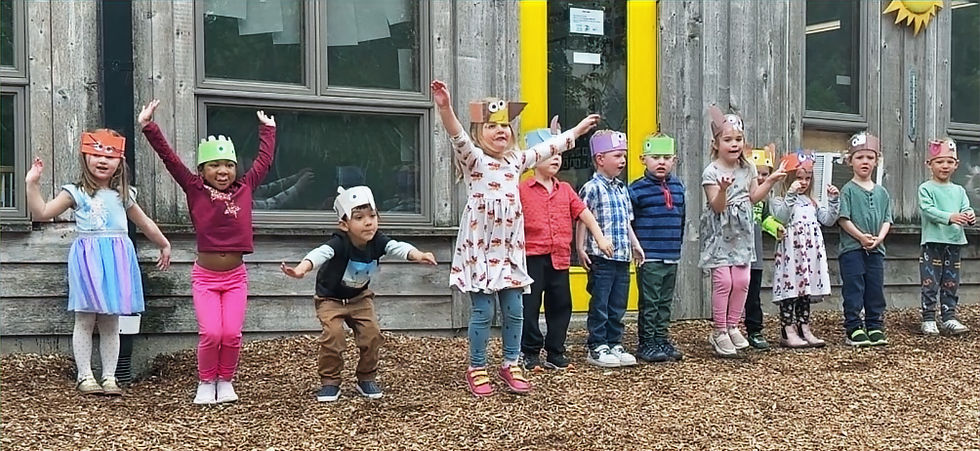

Playful, Multisensory Practice

Because Active Alphabet includes hands-on, multisensory materials—like clay, dot markers, dry-erase activities, and movement-based games—it gives children repeated, meaningful exposure to letters in a variety of ways. That kind of engaging repetition builds both knowledge and confidence.

Final Word

Research has been clear for decades: children who come to kindergarten with strong letter-name and sound knowledge are better positioned for reading success. The Active Alphabet system was developed with that very insight at its core. By teaching names and sounds together, introducing letters in a strategic order, and engaging children in joyful, multisensory learning, Active Alphabet provides the kind of early literacy foundation that research—and experience—tells us works best.

If you're ready to give your students the start they deserve, the Active Alphabet is ready for you.

Research Citations

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chall, J. S. (1967). Learning to read: The great debate. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fry, E. (2004). Helping children learn to read: The Fry phonics program. Huntington Beach, CA: Teacher Created Resources.

Gerde, H. K., Skibbe, L. E., Goetsch, M., & Douglas, S. N. (2019). Head Start teachers' beliefs and reported practices for letter knowledge. Dialog, 22(2). Michigan State University.

Pence, K. L., Justice, L. M., & Gosse, C. (2010). Impact of print referencing on preschoolers’ early literacy development: A randomized controlled trial. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(1), 33–46.

Piasta, S. B., Petscher, Y., & Justice, L. M. (2012). How many letters should children learn? Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 929–941. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027757

Piasta, S. B., Purpura, D. J., & Wagner, R. K. (2010). Learning letter names and sounds: Effects of instruction, letter type, and phonological processing skill. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 105(4), 324–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2009.12.008

Roberts, T. A. (2003). Effects of alphabet-letter instruction on young children’s word recognition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.41

Shaywitz, S. (2003). Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Reading Universe. (n.d.). What the research says about letter names and sounds. The University of Florida Literacy Institute and The Barksdale Reading Institute. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://readinguniverse.org/skill-explainer/sound-letter-correspondence/letter-names-sounds/what-the-research-says-letter-names-sounds

Writing Support & Technology Acknowledgment

This blog post was created using educator-authored content and instructional design aligned with the Active Alphabet system. Writing assistance was provided by OpenAI’s ChatGPT to synthesize research findings and improve clarity. OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (July 2025 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com

Comments